‘You can recognize survivors of abuse by their courage. When silence is so very inviting, they step forward and share their truth so others know they aren’t alone.’

Jeanne McElvaney

Effects of Sexual Abuse During Childhood

Because childhood sexual abuse takes place at a developmentally vulnerable time, and because it is so often perpetrated by a close relative or trusted individual, it leaves behind an indelible mark on its survivors, capable of triggering lasting psychological difficulties reaching corners of the human existence which often run deeper than other forms of trauma (Briere & Scott, 2015). However, there is a path to healing after childhood sexual abuse.

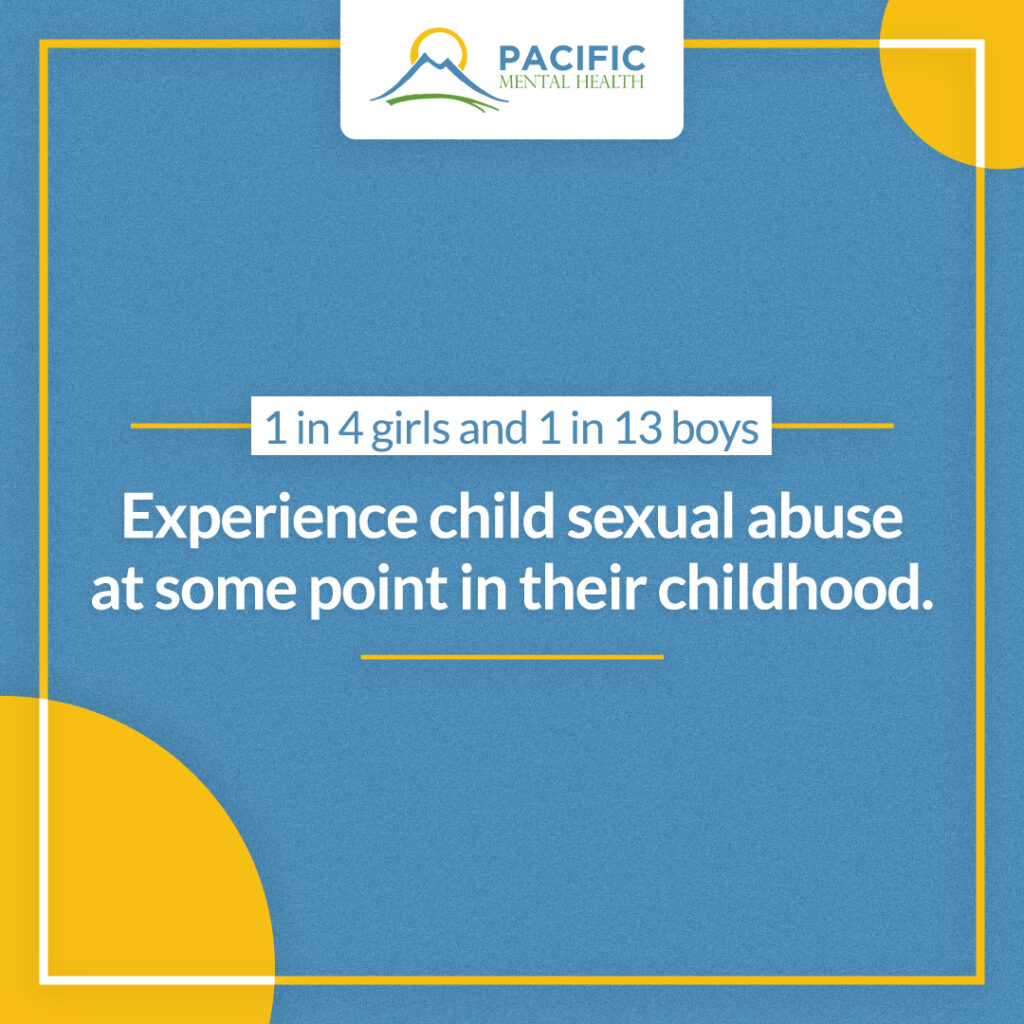

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys experience child sexual abuse at some point in their childhood. 91% of this abuse is perpetrated by someone the child or the child’s family knows (www.cdc.gov). However, we also know that childhood sexual abuse is underreported, indicating that the proportion of individuals within the general public who have experienced childhood sexual abuse, may be significantly greater than current statistics suggest (Hall & Hall, 2011). As a result, oftentimes survivors are left to cope with the aftereffects of abuse with little or no support.

Consequences Caused By Lack of Healing Childhood Sexual Abuse

One of the consequences of an absent framework for healing on the journey of recovery from childhood sexual abuse, is that the abuse can repeat itself in later life in the form of revictimization. Simply put, the presence of childhood trauma exposes its survivors to a greater likelihood of sexual abuse later in life, resulting in a compounding of trauma and its effects, over the individual’s lifespan (Briere & Scott, 2015). Some survivors see this repeated abuse as evidence that they somehow attract or deserve the abuse, further damaging self-esteem.

Greater rates of depression

Childhood sexual abuse is also associated with greater rates of depression (including isolation and self-blame), leading to difficulties externalizing the abuse, and suicidal ideation (Hall & Hall, 2011). Body issues, eating disorders, somatic concerns, anxiety, dissociation and amnesia are also common, as are relationship problems including trust and attachment issues, boundaries, ability to adjust to intimate relationships and involvement in abusive relationships (Hall & Hall, 2011).

Difficulty Distinguishing Danger

Trauma expert, Dr Bessel Van Der Kolk, studied the immune systems of incest survivors and found that compared to their non-abused counterparts, incest survivors have difficulty distinguishing between danger and safety (Van Der Kolk, 2015). On the one hand, the bodies of incest survivors can thus become oversensitive to perceived threat even when there is none, finding it difficult to attain a feeling of safety. On the other hand, incest survivors can find it difficult to distinguish when they are in unsafe situations.

Trickett et al. (2011), conducted lengthy research on the impact of childhood sexual abuse on female development, tracking their subjects over several years. They found that over time, survivors tended to numb out and produce lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol, thereby adapting to trauma, and in doing so, learning (even on a physiological level) to refrain from reacting to distressing situations (Van Der Kolk, 2015).

Repairing The Damage

But there is hope, says Dr Van der Kolk (2015) in his book, The Body Keeps the Score. While childhood sexual abuse may shape the way we view relationships and perceive the world around us, these internal maps can be altered by the presence of positive loving experiences in adolescence and adulthood (Van der Kolk, 2015). Strong familial bonds can also act as protective factors in the development of later psychological problems (Trickett et al., 2011).

Preventing Revictimization

Revictimization is not inevitable, with help and support, survivors can learn to reactivate the natural systems of defense which, as children, they were forced to switch off in order to survive. As we have seen, in the absence of other tools, children often turn to numbing out as a way to survive sexual abuse. Thus, a key function of therapy is to provide survivors with the means to both address the present impact of abuse and to develop coping strategies which have the dual purpose of increasing wellbeing and reducing future risk of abuse.

Managing Feelings Post Sexual Trauma

Learning to experience the feelings associated with the trauma of sexual abuse, both in the mind and in the body, without becoming overwhelmed, is the challenge of recovery (Van Der Kolk, 2015). Through therapy and the practice of techniques that realign the mind and the body, survivors learn to become calm and focused; maintain that calm in response to triggering thoughts, images and sensations; learn to be present and engaged with the people around them; and, learn that they do not have to keep secrets from themselves including secrets about how they have managed to survive (Van Der Kolk, 2015).

Techniques & Therapies

Studies have also shown that techniques such as Prolonged Exposure and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapies are effective treatments in addressing the trauma brought on by childhood sexual abuse (Wagenmans et al. 2018). Survivors have additionally been found to benefit from interventions which incorporate an initial period of stabilization, focused on building emotional regulation and interpersonal skills, before moving on to the processing of trauma (Wagenmans et al., 2018).

Finding Support

Childhood sexual abuse impacts its survivors in lasting ways, but recovery is possible. If you or someone you love have been impacted by childhood sexual abuse, the following resources may be of help:

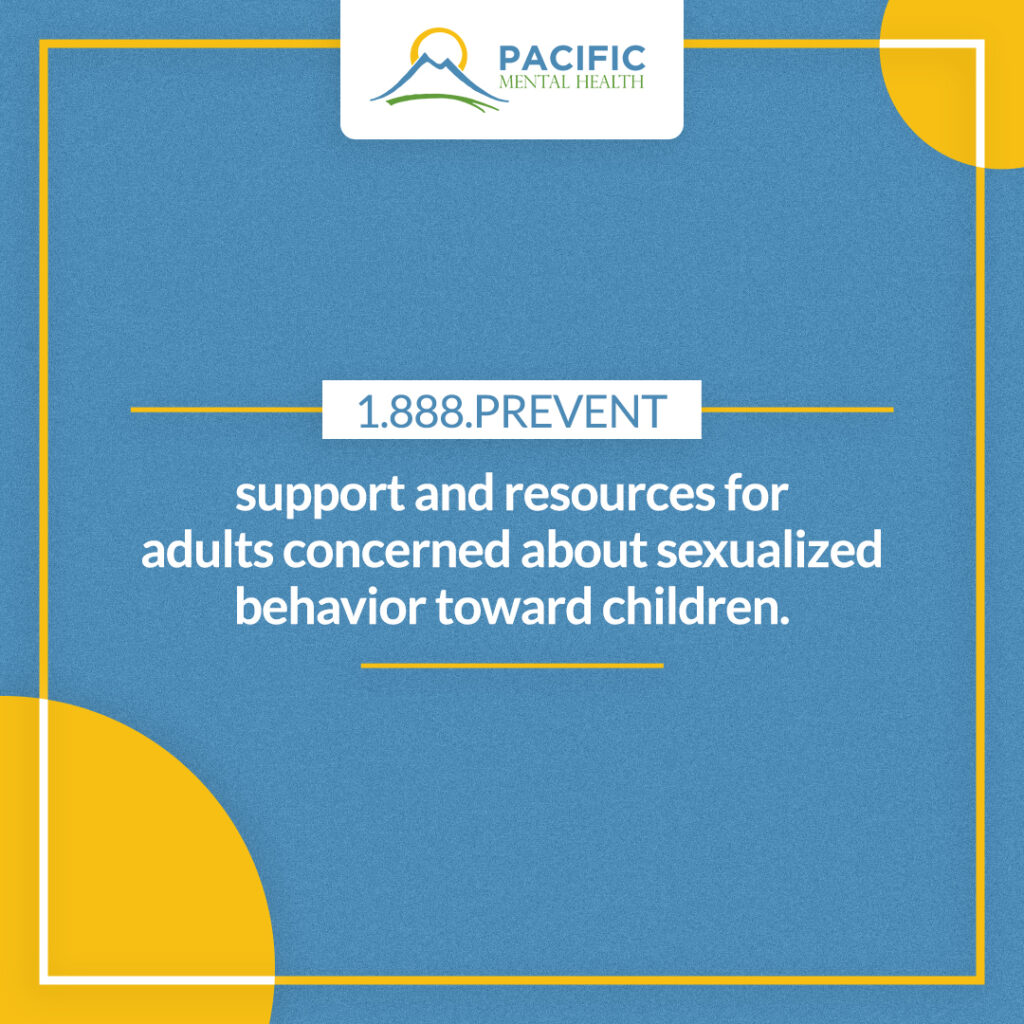

– Stop It Now! This helpline provides (1.888.PREVENT) support and resources for adults concerned about sexualized behavior toward children.

– Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline 1-800-4-A-Child or 1-800-422-4453 call or text 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to speak to trained crisis counselors who can provide assistance in several languages. Online chat is available at childhelphotline.org

References

Briere, J., & Scott, C. (2015). Principles of Trauma Therapy: a guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. Retrieved (December 13th, 2020) from www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Hall, M. & Hall, J. (2011). The long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse: counseling implications. American Counseling Association: Vistas Online. Retrieved (December 13th, 2020) from https://www.counseling.org/docs/disaster-and-trauma_sexual-abuse/long-term-effects-of-childhood-sexual-abuse.pdf?sfvrsn=2

Trickett, P., Noll, J., & Putnam F. (2011). The impact of sexual abuse on female development: lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 453-476, DOI: 10.1017/S0954579411000174

Van Der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., Sleijpen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), DOI:10.1080/20008198.2018.1430962

0 Comments